Few probably recall when Dwight Eisenhower’s public approval ratings plummeted in the sixth year of his presidency after his chief of staff, Sherman Adams, was caught interceding with federal agents on behalf of a Boston industrialist, from whom he had received a rare vicuna coat and several hundred thousand dollars. But every second-term scandal since then has left a more enduring stain that has obscured otherwise notable and lasting achievements.

Behind Watergate, for example, Richard Nixon’s rapprochement with Beijing reshaped US policy toward both China and Japan for the rest of the 20th century. Ronald Reagan was tainted by the Iran-Contra affair, but he also engineered policies that hastened the Soviet Union’s collapse and ended the Cold War. Bill Clinton, impeached for lying about an extramarital encounter with a female intern, erased the unprecedented deficits he inherited and oversaw a period of extended prosperity.

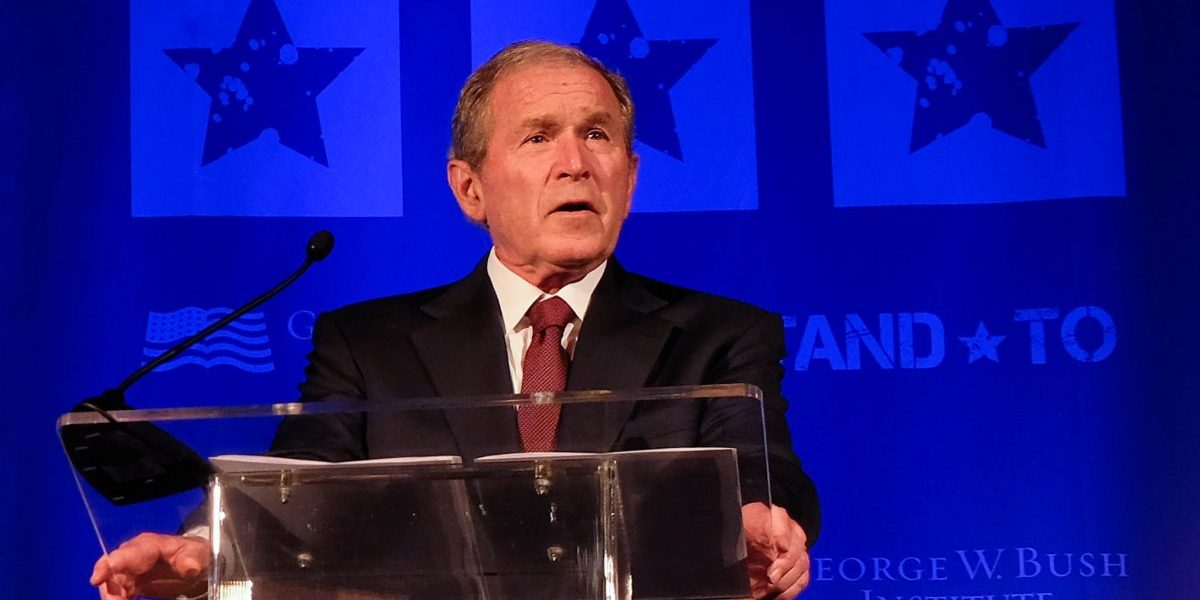

Where, then, is George Bush’s silver lining? Scarcely a year after his re-election and still reeling from his own and his administration’s botched response to Hurricane Katrina, Bush sustained an onslaught of bad news last week: a Supreme Court nomination scuttled; the 2000th US military casualty in Iraq; and, finally, the long-anticipated indictment of one of his most influential advisers on multiple charges of perjury and obstruction of justice, in a case which questions the very credibility of the administration’s justification for invading Iraq.

Behind all this, however, came confirmation that Iraqis adopted a new constitution, perhaps a development of more enduring significance.

The cornerstone of the Bush administration’s foreign policy doctrine is that democracy is the best antidote to global terrorism and other forms of aggression. This raises two pivotal questions: can democracy be externally imposed, particularly in states such as Afghanistan and Iraq where Islam and tribal social structures rooted in centuries of tradition seem so at odds with the principles of contestation of power, free speech and universal suffrage? And is democracy a universal aspiration?

There is growing evidence to suggest that, at least in the case of Iraq, the answer to these questions may be yes.

The new constitution is a compromise, reflecting both an imperative to keep to an ambitious timetable and Iraq’s deeply divided and violent history. Its flaws are rooted historically in the relationship between the once all-powerful but newly disempowered Sunni minority and their Kurdish and Shiite rivals.

True, the constitution committee was swelled by an additional 15 Sunnis with full voting rights midway through the drafting, and some of their concerns were incorporated through amendments. But much of the work was carried out away from the committee, by Shiite and Kurdish leaders in isolated settings. Extensions of the drafting process provided for under the transitional administrative law were not properly sought, yet extralegal delays were taken.

In the end, the Shiite and Kurdish blocs presented the final draft to the transitional national assembly, and it was taken as read without a vote. Key issues remain to be resolved next year by a permanently elected parliament through legislation, a process that favours the majority. Following the national referendum on the document on October 15, the top US commander in Iraq, Gen George Casey, said, “We looked for the constitution to be a national compact, and the perception now is that it’s not, particularly among the Sunni.”

When all the votes were tallied last week, it was apparent that Sunnis failed to defeat the constitution. They needed a two-thirds “no” vote in at least three of 18 provinces. They won substantially more than that in two, but fell 11% short in the third. What may be more important than anything the constitution does or does not say, however, is voter participation trends among the Sunnis themselves.

Back in January, Sunnis boycotted elections for the transitional government, believing the political process unfairly favoured the majority Shiites. They subsequently realised their mistake and begged access to the constitutional committee. Their participation in the constitutional referendum earlier this month – reportedly 93% in the Sunni stronghold of Fallujah, for instance – confirms a shift in strategy.

As the minority faction of ousted dictator Saddam Hussein, Sunnis have provided the local base of a largely foreign-fuelled and extremely bloody insurgency. Yet they rejected warnings from foreign jihadists to protest the referendum and risked their lives to vote, apparently recognising that the best way to safeguard their interests is through ballot forms rather than car bombs.

How, then, can this be nurtured?

First, the constitution paves the way for elections of Iraq’s first full post-Saddam government and parliament on December 15. Those who are elected will govern for the next four years and have the responsibility for filling in the legislative gaps identified by the constitution, including determining the basis of such sensitive issues as regional autonomy, property rights and the internal movement of people, goods and capital. The inclusion of all factions in the new parliament is the only way to ensure that minority groups have an opportunity to press their interests, and is therefore a crucial prerequisite for future stability.

The international community, working through the UN mission in Iraq, should make every effort to ensure the best and widest possible representation in the new government by encouraging and enabling all Iraqis to participate in free and fair elections.

Second, the coalition forces must begin to show that their presence is more about nation-building and less about occupation. A measured and gradual withdrawal based on clearly identified milestones of progress toward self-governance and stability would signal that Iraqis hold the keys to their own future.

Washington has committed many costly errors in Iraq. It is possible that the remainder of Bush’s presidency will be mired in deepening controversy about questionable justifications for the war.

But there is no undoing what has been done, and while full-blown civil war and fragmentation remain real and present possibilities in Iraq, so does the demonstration of two highly desirable ideals: that inclusiveness is a more effective political means than violence, and that, given a chance, Islam and democracy can be reconciled. In the broader project of political reform across the Middle East, these may yet become the greater part of Bush’s legacy.